Papa Osmubal’s “A Bum’s Demise” [Read the poem here]

(First published in Issue #10 of Cha, this poem was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2010.)

–This post is written by Tammy Ho.

Papa Osmubal’s “A Bum’s Demise” begins with ‘He is dead’ (L1), which reminds one of these lines from WH Auden’s “Funeral Blues”: ‘Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead / Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead’. Although Osmubal’s poem is a very different kind of elegy, it is one that finishes with a similar loving appreciation.

The deceased in Osmubal’s poem is a nameless bum, an unusual subject for tribute. At several points in the piece, the persona draws the reader’s attention to the difference between the bum and the rest of their group: ‘He left in mysterious and unexpected / fashion, leaving us all asking’ (L3-L4), ‘After weeks in a public infirmary, he showed up / much earlier than us all’ (L9-L10) and ‘”Man lives once, and dies once,” he said, / guffawing like he was mocking us all’ (L19-L20). The use of pronouns in these lines points to the “he vs. us” dynamics. Perhaps this distance is the result of the group’s admiration for the man; it is also possible that there is a sense of fear that they may follow him to the grave.

While it is suggestive that the bum is different from the other members of the group, it is clear in the poem that the persona and his pals care about him enough to feel intrigued by his death. They wonder if there was some rhyme or reason to it: ‘He left in mysterious and unexpected / fashion, leaving us all asking / And wondering as though his demise / was a riddle that needed answering’ (L3-L6). We are told that the tramp had been released from the infirmary the day before, and he had gone on one last overnight drinking binge only to die at dawn. The mystery is not so much the circumstances, as it is his motivation for giving up on life. Is his decision to leave the world based on something that happened to him in the hospital? After all, the first two lines of the poem are explicit about his troubled organ: ‘his liver turned / Hard and bone-dry like a stone’. Or does his determination to die arise from something else, a secret or the collective disappointments of a life?

The bum might not have been a rich person, as evidenced by his having used a public hospital, but he is hardly uncultured. At the beginning of his last night on Earth, we see him partying in style. When the others arrive at the scene, he is seen ‘reading Verlaine, reading / Poetry in his favourite corner, silently filling / his lungs with Havana cigar smoke’ (L10-L12). The reference to the French Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine provides some kind of clue to the background of the bum: Verlaine was also a bum of a sort, spending the latter years of his life in poverty plagued by alcohol and drug abuse. Osmubal’s character parallels the poet, and the depiction of his vices is somewhat romanticized: ‘a box of cigar’, ‘a glass with a generous whisky’, poetry, and an occasional woman, although that night he declines their company because he does not ‘want to be a father again’ (L16). One wonders why the bum is reading poetry and what poetry means to him — is he perhaps a failed poet? Or a failed scholar? Perhaps, without success of his own, he has slipped into alcoholism. Note the ‘again’ in “”Don’t give me girls tonight,” he blurted. / “I don’t want to be a father again!”” (L15-L16) suggests that firstly, the bum has a great sense of humour, and secondly, he might have previously sired at least one child — is he also a failed father? Do any of these offer an explanation for his generally depressing lifestyle?

The bum’s death comes at dawn ‘when the gang / felt they had had more than enough’ (L21-L22). In other words, he enjoyed his night by living, or rather dying, to the fullest, and bid farewell to the world at sunrise. The final stanza of the poem underscores that ‘He did not go the usual way, he went / towards where the sun was rising’ (L23-L24). Contrary to the normal symbolism of death being equated with darkness (think, for example, Dylan Thomas’s “Do not go gentle into that good night“), for Osmubal’s bum it is the night of partying that stands for life, and the morning after is the time to die. It also suggests a new beginning and perhaps a sign of relief to be walking out of the darkness into the light. The word ‘usual’ — used two times previously: ‘The night before we were all late / for the usual overnight binge’ (L7-L8) and ‘As usual it was almost sunup when the gang / felt they had more than enough’ (L21-L22) — sets up a routine for the group. This pattern is broken by the bum’s death: ‘He did not go the usual way’. He went his own.1

That the bum did not go the usual way points to the sense that he was admired by the others in the poem. For them, he was an original, someone willing to leave this world on his own terms: ‘This man, one can say, did not know how / to live, but he sure was darn good at dying’ (L13-L14). The persona’s tone of respect and affection is unmistakable here. We will never know the reason the bum has decided to end his life at that point. However, the persona seems to revere this man who although has perhaps wasted his life, certainly knows how to go out in style. He indulged one last time, enjoying the beautiful things in life: his favourite piece of poetry, a box of cigars, whiskey with his friends and lastly, the stunning sight of sunrise.

Surely this is more than a bum’s demise.

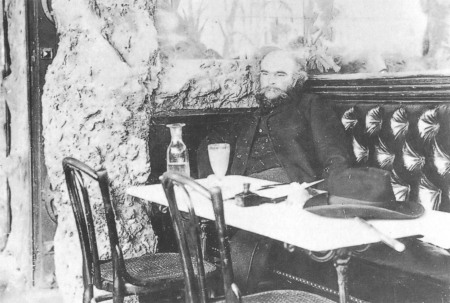

Paul Verlaine, photographed by Dornac

1This reminded me of Nicholas Royle’s discussion of the death drive in The Uncanny (2003): ‘It is not just that deep down inside — whether we realise it or not, whether we like it or not — we all want to die. More precisely, we all want to die in our own way, on our own terms, according to our own trajectory, in accordance with ‘detoures’ of our own devising, in keeping with a certain ‘rhythm”. (93)

Also read A Cup of Fine Tea: Papa Osmubal’s “At Hac Sa Beach”.

Papa Osmubal writes from Macau. His works, visual and literary, appear in numerous places, online and hardcopy, most recently in Bulatlat and Poor Mojo’s Almanac(k). He writes regularly foreK! (electroniKabalen / electroniKapampangan / electroniK…). He is currently working on a collection of modernist papercuts for his planned solo exhibition tentatively called ‘Nocturnal Voice’.

Papa Osmubal writes from Macau. His works, visual and literary, appear in numerous places, online and hardcopy, most recently in Bulatlat and Poor Mojo’s Almanac(k). He writes regularly foreK! (electroniKabalen / electroniKapampangan / electroniK…). He is currently working on a collection of modernist papercuts for his planned solo exhibition tentatively called ‘Nocturnal Voice’.

October 17, 2010 at 12:45 am |

Donna said: Nice analysis and *excellent* poem. Enjoyed both. 🙂

October 17, 2010 at 11:07 am |

I love the poem and the commentary too. Lovely work!

October 17, 2010 at 9:36 pm |

I agree that this is one of Cha’s best poems this year, and deserving of a Pushcart nomination. The poem is charming. I love poems that never forget that their biggest responsibility is to entertain us.

Not only is there a sense of mystery surrounding death but that of the bum himself. Why not a bum? Aren’t all the people we know filled with secrets and mysteries? Few poems suggest the mystery of others so well.

It’s interesting that if the bum is giving up on life(for the reasons cited in the review) that he walks towards a rising sun as his last gesture. It suggests a man who has lived as generously as the whiskey he pours out, and is tipping his hat one last time to life.

A lovely poem.

October 17, 2010 at 10:24 pm |

Dear Tammy,

Many thanks for everything. I have now started to find meanings from what I am doing as a writer of verses.

Best,

Papa Osmubal

October 18, 2010 at 8:10 pm |

I enjoyed reading this poem very much. I also liked the analysis, especially on the dying man’s final indulgence, enjoying his favourite tipple, poem/poet, his friends’ company. I have only a couple of points to add.

The poem reminds me of earlier artistic circles where Bohemia was a country, a destination, a landscape inhabited by artists; its roads reportedly leading to “the Academy, the Hospital, or the Morgue.” The word “bum,” referring to a tramp or vagrant, someone who uses the resources of others, or someone who concentrates on a particular activity, such as a beach bum (in this case poetry?) is however denigrating, separating the person using it from the other. By referring to the dying man, perhaps a “poet” as a bum, the narrator distances himself from him and his way of life, while at the same time remaining the man’s contemporary, drinking companion and friend. There is also the implication of more than a mere friendship in the “no girls tonight” and in the use of Verlaine’s name (conjuring up his tumultuous relationship with Rimbaud).

In this sense, there is a mirroring process involved through which the reader, Verlaine, the possible “poet” of the poem, and the narrator become entangled in a distorted mirroring. I see the use of the word ‘bum’ as being vital in creating this illusion.

The narrator seems to be “reading” the dying man like the dying man is reading Verlaine. And in this multi-level mirroring, we, the readers, are reading a poem about a narrator “reading” the (possible) poet/bum who is in turn reading Verlaine. In this hall of mirrors, while the dying man’s liver is shown to have turned to stone, the main injury is to his heart. His friends are not emotionally close to him (his illness and death a mystery to them, unexpected); his son, lover, family absent from his deathbed.

We enter the space and time of the poem, while at the same time we observe through the lenses of our own culture the self-destructive decline of the man as a ‘bum’ (not as father, poet, whatever else he was) dying of an alcohol-related problem (the hard liver) in an alcoholic haze. The narrator keeps a respectful silence over the self-destructive behavior of the dead man – he notes the “guffawing like he was mocking us all.” Or does he not quite see the problem? Maybe he shares it? (the sunups). Or are we invited to reflect more into the destructive friendship of the two men? I read that Verlaine had knife fights with Rimbaud, and only once there was a cut, they stopped fighting and went to the pub! I will continue thinking about this poem. Haunting!

A very powerful poem with multiple levels of associations and meaning, reflecting on life and society as well as on the lives of the artists, their sundowns as well as sunups… I wish I knew who it was who talked of the road leading to “…the Academy, the Hospital, or the Morgue.”

October 19, 2010 at 4:32 pm |

Dying is no fun

Though celebrating death

Transforms the suffering

Gives it meaning

Where before there was only pain

But know this,

It’s only change

Another turn in the spiral

Of Life and Death

You speak of me

As if I’m not here anymore

Calling me a bum

Calling me a poet

Or an alcoholic

As Jack Sparrow would say

“Sticks and Stones, love”

But I’m still here with you

Or should I say

We are all here with you

We spirits of the dead

Thou you, in your fear

Call may us ghosts

As if we were monsters

That you could exorcise

We called for spirits in life

Never guessing

That, ‘like calls like’

Have you any idea

How many spirits

Surround you now

We are here with you

Even if you don’t see us

Call us dead if you like

Though, you the ‘living’

Seem more like dreams to us

The Chinese know better

They feed us and house us

Send us what we want and need

And most importantly

They speak to us

Letting us know

That they still care

yamabuki

October 22, 2010 at 4:42 pm |

What a pungent, beautiful poem…